What's with all the borders? (1)

What are countries, borders, nations, and nationalities? Let's think together through art, with Chisai!

I was born in Okayama, a prefecture that has produced many modern painters, and lived in Tokyo for about 20 years after entering university. I moved to Kyoto about 13 years ago. In Okayama, I was surrounded by modern painters, and in Tokyo, I pursued contemporary art. Since moving to Kyoto, instead of following the stagnant art scene in Japan, I've been frequently flying to neighboring countries and regions on low-cost carriers, for about the same price as a Shinkansen ticket.

From the beginning, I didn't want to simply "go see an exhibition" or do the typical tourist things like eating good food or seeing beautiful scenery. I wanted to connect with artists in nearby countries and regions, to understand what they were thinking and how they were creating their work. What should art be doing in our time? What can it do? And how can I be a part of it? These were the questions that drove my actions.

One of the turning points was a paper I wrote in English two years ago. A university in Palestine was seeking submissions on the theme of "New Japanese Art History." It was my first time writing a paper in English on my own, and it was accepted. I was invited to the symposium, but it was postponed due to the outbreak of war. However, that experience opened my eyes to the possibility of writing and presenting in languages other than my native Japanese.

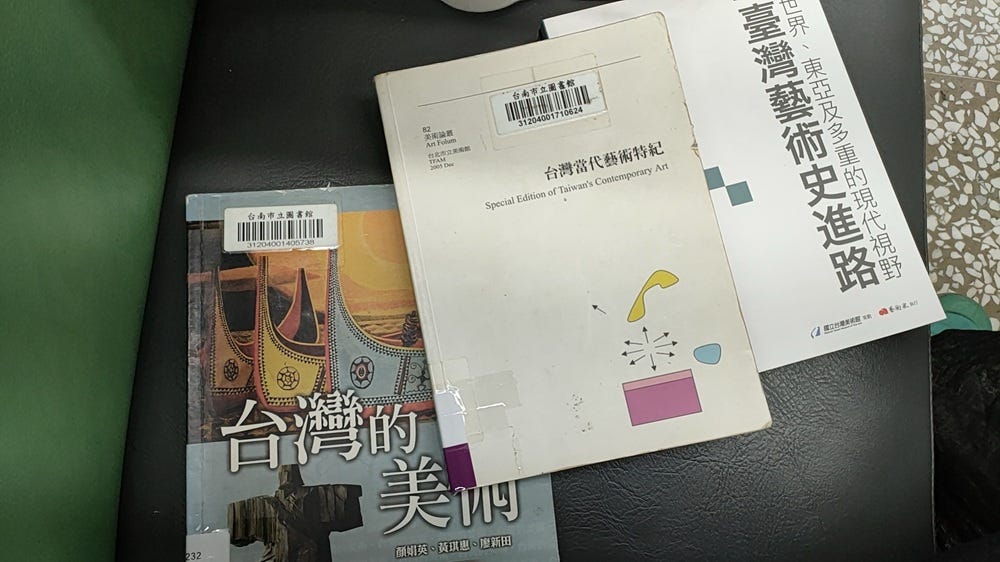

Then, last year, I took a gamble. I applied for a paper competition in Taiwan using Taiwanese Mandarin, which I had been studying for about 10 years. Fortunately, I got the opportunity to present at the Tainan Art Museum in July. When the staff asked me what language I would be presenting in—Japanese? English?—and I answered "Mandarin," I felt a little proud. A university professor who was there clapped and praised my presentation, saying, "A Japanese person spoke our language, and the content is interesting!" Thanks to him, I was able to join the Taiwan Art History Association.

As the end of 2024 approached, I was writing a paper in Japanese about an artist who traveled between Japan and Taiwan. I got so caught up in it that I forgot to apply for a paper competition in Taiwan. But the one submission I did make, to Chiayi University, was accepted, and in May, I successfully presented a paper on a contemporary artist.

Soon after returning to Japan, I received the peer review feedback for the paper I had been writing in Japanese since the end of the year. I hit an unexpected wall. The feedback brought up the phrase "the context of the Tokyo School of Fine Arts"—a distant, historical point that had nothing to do with what I had written. It was then that I realized my question might not reach the narrow world of Japanese art history.

Feeling deeply discouraged, I instinctively knew I didn't have the time or energy to rewrite the paper according to that feedback. So I quickly translated the peer review into English and Mandarin and sent it to two friends. They immediately responded with laughter.

One was a Taiwanese researcher, who found it amusing that someone would compare a painter from decades ago (the 1960s-80s) with an artist working right now in my paper. The other was an American editor who had recently received an unpleasant peer review himself for an article about art in a science journal. He deeply empathized with my situation.

Next time, I'd like to use this paper as a foundation to think about the nature of art (history) both in the past and in the future. In Japanese, I call this "Doko Doko Art (History)." "Doko" means where, anywhere, which place. We're living in the 21st century, so the question is, where is "here" anymore?